Or, how to party like it’s 1984

By the end of this terrible year of 2016, the world is fully in the embrace of Hygge-mania. Books, blogs, youtube videos, newspaper articles, all espouse the virtues of the Danish concept of frilly cosiness, pillow-hugging friendliness and cake and cocoa by candlelight. And what’s not to like about the idea of cutting yourself from the all the evils of the outside, and shielding yourself with blankets and woollen jumpers from the encroaching darkness?

Except Hygge is an illusion. An aspirational lie. It only works if everything else works — if you live in a nice, well-organized country like Denmark, surrounded by beautiful Scandinavian people, your candle-lit life supported by a generous welfare state. This isn’t how most of us live — and, the way things are going, the Hygge concept will grow further and further away from reality, another unachievable ideal, made only to stress us out and feel miserable, like being thin or feeling good about the party you voted for.

There is another way. If you want to borrow a way of life from another people used to dealing with cold, dark winters, a way of life that is easier to achieve and more suitable to how things are in this post-Brexit, post-Trump, look no further than to the Slavs — in particular, the Poles.

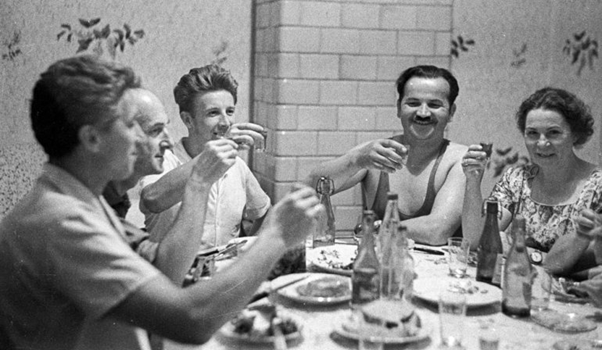

In the coldest nights of serfdom, Partition, Communism, and post-Communist chaos, the Poles have developed ways to cope with both the harsh weather and the harsh political climate. In the centre of this way of life stands the concept of DOMÓWKA (pron. Domoovka) — literally “House Party”, but not the kind you would imagine. Here, in a few steps, is how you can try to replicate this concept at your own home, when everything goes to hell and the nuclear winter makes global warming a distant memory.

1) SETTING

It’s a house party, so of course everything happens in a house — but forget a three-bedroom villa in the suburbs. The closer your house is to a council estate flat, the better (an actual estate flat is ideal). And it doesn’t matter how big or small the flat is — all that matters is that you have a kitchen and a dining room, for this is where most of your Domówka will take place.

For reasons lost in the midst of time, the kitchen is the heart of Domówka. It could be the atavistic longing to be near the fireplace — replaced here by the four-hob oven — or it could be the vicinity of the fridge, but no matter where the guests are when the party starts, eventually all the conversation gravitates towards the kitchen. It makes sense when you think about it — the kitchen is cozy, easily heated, provides access to supplies and fresh water, and often has the best acoustics in the house outside bathroom.

Lighting should be subdued — a night-light is enough. Dimmer switch is decadence. Of course, candles are best — not only because they provide coziness, but also because when the power runs out in the middle of the party, due to the crumbling infrastructure unable to deal with the freezing cold, you won’t even notice.

2) DRINK

You probably guessed already that the drink of choice here is vodka — Polish or Russian only, none of that fake French stuff. Only the heat of vodka can truly stir the hearts, loosen the tongues, and beat the cold of a northern winter out of one’s bones. Vodka drank straight, ice-cold — so cold, preferably, that it oozes out of the bottle like oil. This can only be achieved with enough preparation, so only applies to the first batch (see Restocking).

Any other alcohol — beer or wine — is to be used only in the form of “liquid tapas” — variously known as Zapojka or Zapitka — to cleanse the palate between vodka shots.

Soft drinks are fine — the cheaper, the better, though Coca-Cola is still a classic stalwart from the days when it represented the “evil West” and an opposition to whatever regime ruled the country. Mixing vodka with the above is fine if you’re feeling fancy, though only when used as Zapojka/Zapitka.

The only acceptable hot drink is tea — strong, black, with a slice of lemon, drunk from a glass. Have plenty of it ready. Biscuits are optional — home-made cake is obligatory.

3) FOOD

Speaking of cake, the food is not to be forgotten. Zakaski or Zagryzki(Zakuski in Russian), which is a Slavic variety of mezze, is a culinary art in its own right. The prevalent taste sensation is sourness, and fattiness, both helping to beat the side-effects of all that vodka. So sour-pickled gherkins, of course, and pickled herrings in oil or sour cream, and pickled mushrooms… Then lots of mayo — on eggs, in vegetable salad, on cured meats. If you want a more Eastern experience, have some salo — cured pork fat. If you’re feeling adventurous, put things in aspic, though since that requires a lot of preparation it’s becoming less and less popular.

Pickled and fatty foods, cured meat and cheese, are all things that keep well, which is another plus in our dystopian future — you can even stock the leftovers from one Domówka to another.

4) CONVERSATION

We’ve secured the location, drink, and food — but what are we going to do at this strange party? Not dance, obviously. Talk — but what about?

The conversation topics at a Domówka are deep and tough — the deeper and tougher the better. You can’t be whimsical when you’re downing shots of vodka — this isn’t your auntie’s sherry soiree. Football scores is at light as it gets, at first — but then we’re moving on to the real stuff: politics, history, religion.

It used to be that in the West topics like politics and history were a taboo in polite company. This is a privilege the Poles, and most of their Slavic brethren, never had — and, in recent years, it’s become obvious that it’s the only conversation worth having, anywhere. What else can you talk about when Trump is president, when Putin marches through Syria, when Farage’s grin is plastered all over your TV screens? And politics is steeped in history — you have to understand the past to explain the present. Poles like to think of themselves as experts in every subject, but history is everyone’s true hobby. So as the vodka flows, the conversation will flow from recent elections, to the Communist era, to 19th century oppression, all the way to the arrival of first Christians on Polish soil who, depending on your worldview, are either to blame or to credit for everything that’s happening currently.

These conversations are such a crucial part of the Polish soul, that they are even mentioned in poetry — Poland’s chief poet, Adam Mickiewicz, coined the term “Polish Nightly Conversations” in 19th century, which had since entered the vernacular.

5) MUSIC

At any party, choice of music is important — at the Domówka, no less so. What music is best for vodka and pickles? The answer may not be obvious to you, but it’s obvious to any Pole: shanties, folk and poetry.

Here’s another old Polish term: “sung poetry”, also known as “gentle music” or “author song”. It’s a pan-slavic phenomenon, originating with Soviet Bards – a mixture of French chanson, Russian poetry, Celtic folk and scouting songs. Leonard Cohen, Vladimir Vysotski, Jacques Brel are the godfathers of this music genre. Sombre, serious, flowing, often, again, with political overtones. Born as a form of escapism back in the Communist era, the songs tell of a gentler, imaginary land, of nice, decent people, freedom and fresh, unpolluted air. Shanties and Celtic folk stem from the same need of escape — when all else around you is dreary, cold and dark, sometimes all you have left is to imagine yourself on a tallship off the coast of Ireland. (nb. the popularity of these songs goes a long way to explain why, after joining the EU, so many Poles flooded Ireland — it was as if suddenly Neverland turned out real.)

If your Domówka is going well, at some point in the proceedings, one of you might want to pick up a guitar and start making ready for a sing-along. This may be a good point to pause the party for Restocking.

6) RESTOCKING

A key moment in every Domówka is when the vodka runs out. It is considered bad form to have “enough” alcohol to last all night — it suggests you imagine your guests drunkards, which they most certainly are not.

This is not a moment to despair. On the contrary, a pause is necessary for the party to continue in peace. What you need to do is mount an expedition to restock the fridge. In the old days, this meant finding out a neighbour stocking a private stash of alcohol, often contraband or home-made, in a melina (private speak-easy). These days, you need to seek out a 24h off-licence or, even better, a petrol station.

The restocking expedition is an essential reset button. It’s a chance to cool heads heated up in the middle of a political argument; an opportunity to let the cold wind freeze the alcohol from your veins; a moment to appreciate the quiet of the winter night, look out to stars and realize the insignificance of our problems in comparison with the vastness of the universe. Without this pause, the guests at Domówka would soon degenerate into drunken, slurring stupor.

7) TRUST

What happens at Domówka, stays at Domówka.

Domówka is a one-night carnival, a place and time when established rules and relationships are suspended. There’s no other way. With the amounts of alcohol drunk, with the sea of existential despair that needs venting, nobody can be held responsible for their actions. Whether it’s an ideological argument gone sour, or a sneaky, desperate tryst in the bathroom, all is forgiven in the morning — or whenever the headache passes. The one thing that is not tolerated at the Domówka is violence: this is where the line is drawn. Violence is for the enemies, there’s no place for it among friends.

This concept of trust makes Domówka what it truly is — a way to survive the unsurvivable, to escape the unescapable.

8) ŁAPU-CAPU

(pron. Wapu-Tzapu) This is another important Polish concept, one that requires a whole separate article, or a book, and one which stands at the heart of Polish aesthetics, much as wabi-sabi stands at the heart of the Japanese one. Another similar word is “prowizorka”, or doing something as a shoddy, makeshift, temporary one-off: a concept crucial in a land through which foreign armies have marched for centuries, burning and pillaging everything in their path. Like the Japanese wood and paper houses, everything in Poland is made not to withstand the pressures of history, but to yield to them, and be easily replaced. The less attention to detail, the more make-shift the solution, the better. As the old Polish saying goes, “prowizorka holds out the longest”.

In Domówka terms, this means — don’t sweat it. Don’t prepare too hard. In the end, it’s the mood that matters, not how nice the mayo is spread on your eggs. As long as you have enough alcohol, and enough friends to drink it with, all else will come on its own. Life in our incoming dystopia will be hard enough without having to worry about things like precision and sturdiness. Embrace the Łapu-capu — it may be the only way to survive what’s coming.